It feels like things have been quietly building lately.

Not in a dramatic way – more like steady momentum.

The Walkbook, Reimagined

I’ve been spending a lot of time working on the digital Walkbook for Sheldrake. What started as an idea has slowly turned into something much more concrete.

Over the past few weeks, I’ve typed and reformatted the entire original paper version, reorganized it for clarity, created categories and strengthened “learn” sections so each stop really emphasizes observation, and scanned all of the original drawings. My goal hasn’t been to replace the old walkbook – it’s been to preserve its spirit while making it more accessible and interactive.

I’ve also been thinking bigger.

What if each station had a QR code on the wooden posts? What if the trail map on the website became clickable, so visitors could explore before or after they walk? What if we used dynamic QR codes so we could actually track engagement and understand how people are using it?

This part excites me – not just the writing, but the systems behind it. Thinking about implementation, IT coordination, signage approval, real-world logistics. It’s one thing to have an idea. It’s another to make it function.

And I think I’m learning to enjoy that middle space.

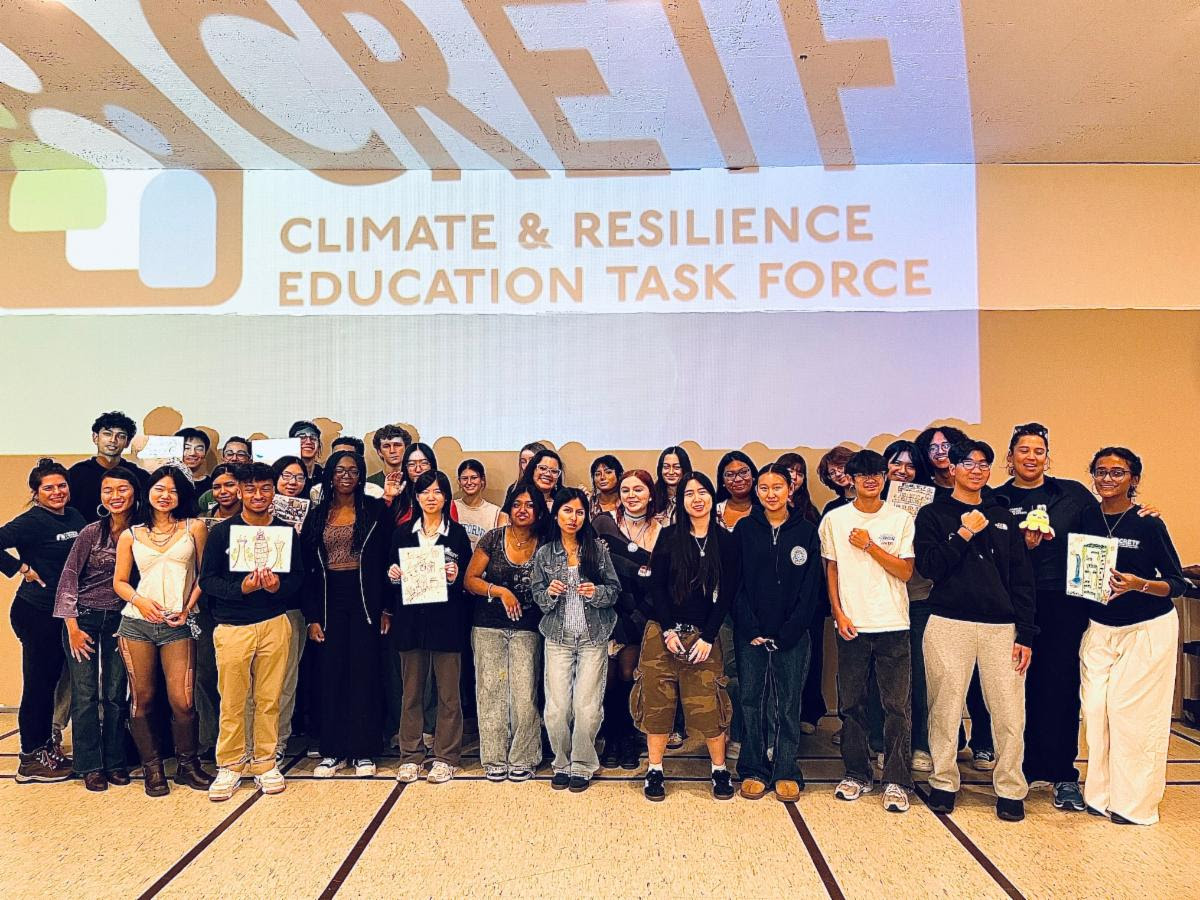

Salt Marshes and Students

Even though I couldn’t attend the most recent Sustainability Collaborative meeting, I read through the notes – and the big takeaway for me was some students’ Project Salt Marsh.

They worked with middle schoolers to test water quality at a local conservation area, taught them about marsh grasses and flooding, and helped them understand how fertilizer runoff affects bacteria levels. Some of the younger students didn’t even know the conservation area existed.

That stuck with me.

So much of environmental work is simply helping people notice what’s already there – the marsh filtering water, the grasses reducing flooding, the invisible systems keeping communities functioning. It reminded me why local education matters so much.

The meeting also touched on Safe Routes to School, Earth Day planning, compost giveaways, and continued conversations about roadway redesign. It’s interesting how sustainability in town meetings spans everything – from salt marsh bacteria to traffic striping to storm drain decals.

It’s never just one issue.

Project Green & Earth Day

At school, we’ve started planning for a county-wide Earth Day exposition happening in May. Multiple schools will be involved, and it already feels bigger than our usual events.

Last year, the expo was much smaller – just a few local organizations and maybe two or three schools presenting in a local library. It was meaningful, but contained. This year, if participation keeps building the way it looks like it might, it could be exponentially bigger.

And it’s just cool to see that kind of growth.

There’s something powerful about watching an idea expand beyond its original scale – more students, more conversations, more collaboration – this time in our county’s center, rather than just a local library. It makes sustainability feel less like isolated efforts and more like a network forming.

More updates once it actually happens – but it’s exciting to think about students across the county showing up for something shared.

Sheldrake (Beyond the Walkbook)

I also recently drafted a trail safety blog for Sheldrake – practical things like staying on marked trails, protecting yourself from ticks, learning to identify poison ivy, and keeping wildlife wild. Writing it made me realize that sustainability isn’t just about policy or data. It’s also about care. About protecting places by teaching people how to move through them responsibly.

The Walkbook and the safety guide feel connected – one invites exploration, the other helps protect it.

Research, Music, and Breathing Room

On a more personal note – I’m currently off from school.

Junior year has been intense, but I’m finally finishing up an independent research paper I’ve been working on:

The Interaction of Population Density and Flood Infrastructure in Urban Flood Risk Areas.

It looks at how flood damage increases with population density but decreases when strong infrastructure – especially green infrastructure and proactive planning – is in place. It’s basically a synthesis of how cities can adapt smarter, not just react.

Submitting it soon feels like closing a chapter I’ve been carrying for months.

And outside of all that, I’ve been practicing piano a lot – preparing for competitions, a master class, maybe even our school talent show. There’s something grounding about sitting at the piano after thinking about flood models and municipal planning all day. It reminds me that creativity and sustainability aren’t separate parts of me.

They’re both ways of paying attention.

Lately, I don’t feel like I’m chasing big achievements. I just feel… in motion. Working on things that matter to me. Learning how ideas turn into systems. Trying to balance ambition with rest.

More soon.